Rabbi

Rabbi David Bockman

David Bockman grew up in California and was ordained a rabbi at the Jewish

Theological Seminary in New York in 1986. Since that time, he has served pulpits

in Kansas City, Maryland, New Orleans and North Carolina. A fifteen-summer

veteran of Camp Ramah, Rabbi Bockman enjoys an innovative and creative approach

to Jewish life.

As a Seminary student, he won the Henry Fisher prize in homiletics, the Solomon

and Rose S. Lasdon prize for creativity in translating Guys and Dolls into

Hebrew, and first prize in the UJA/Morris Kaplun university essay contest. Rabbi

Bockman has studied physics, linguistics, music and literature as an

undergraduate at the University of California at San Diego. In addition to his

Master of Arts in Jewish Studies and rabbinic ordination, he has completed

course work towards his PhD in Jewish Philosophy, focusing on the post-modern

French Jewish philosopher Emmanuel Levinas. He has taught Jewish History at the

University of New Orleans, and developed adult courses on Jewish philosophy and

the musicals of Stephen Sondheim, oppression, and the nexus between 20th century

math and Judaism.

Rabbi Bockman is proud to be married to Vicki Hyman, a newspaper reporter who

grew up in Monsey, NY. Their delightful son, Theo, contributes to services with

his humor and love of Judaism. They enjoy living in Bergen County and facing the

challenges of ready access to kosher food and abundant Jewish and Israeli

culture.

Rabbi Bockman, since becoming the spiritual leader of Congregation Beth Shalom, has brought great vitality to all Shabbat and Holiday services and by leading many adult classes at CBS. There's an Israeli dancing class, Adult Bar/Bat Mitvah classes, Hebrew Poetry, among others.

He is known for playing jazz trumpet and shofar in klezmer, gospel and jazz groups, including performances at the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival and the House of Blues. His Jewish musical projects have included the vocal quartet ‘Beignet Yisrael’ and the smooth jazz trio ‘Rabbi, Russian and Blonde.’ He even performed a Duke Ellington piece at Congregation Beth Shalom's Interfaith service for Thanksgiving.

Purim 2011 Megillah Music

Jam

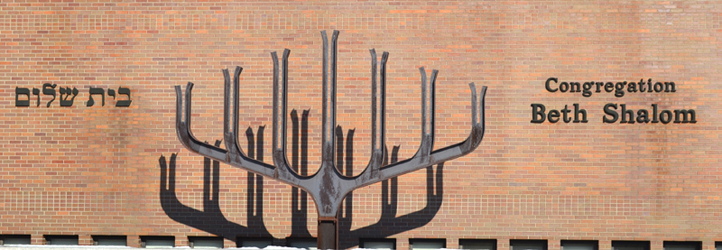

Congregation Beth Shalom Pompton Lakes, NJ

"Finding Meaning Through Music" Lecture

May 18, 2011

Rabbi Study Series YM-YWHA Wayne, NJ

Part One

Part Two

Part Three

________________________________________________

Parshat Chukkat: Tragedy in a TripTik?

of Passaic/Bergen County, NJ

Published: June 13, 2013

This week’s Torah portion contains quite a lot, including the rock-striking incident, the healing of a plague of biting snakes, and the deaths of both Miriam and Aaron. But it also contains a very short song, considered (strangely) by the Talmud to be one of the three major songs in the Torah. (The other two are the Song at the Sea and Ha’azinu, both, like this week’s, prefaced by the words “az yashir, “then sang....”) The Talmud even specifies that those three songs were sung, alternating, every Shabbat afternoon before the late afternoon sacrifice (mincha) as the day was waning.

It is certainly clear where each of the songs begin, and where the other two songs end. But our little song about a well springing up, while clearly beginning in Numbers 21: 17 ( “az yashir Yisrael et ha-shirah ha-zot, ali be’er … — then Israel sang this song, ‘spring up, oh well…’”), does not necessarily end with references to the well, contained in that verse and the next. Instead, the subject seemingly changes halfway through verse 18, becoming a travelogue — the sort of travelogue most people tend to skip when reading through the Torah: “…and from Midbar to Matanah. And from Matanah to Nachaliel, and from Nachaliel to Bamot. And from Bamot to the valley that is in the field of Moab, the top of Pisgah, overlooking the Yeshimon.” It is only here, at the end of the fourth verse, that the Torah inserts a space, seemingly concluding the quoted song.

The Torah brackets the poem in this manner, although most translations set off the first verse-and-a-half as clear “poetry mode,” returning to “run-on narrative mode” for the travel verses, indicating those editors’ decision that the latter verses were not intended to be part of the poem or song. Are those verses part of the Ode to the Well? Do they rise to the level of art? Or are they merely a plodding recitation of place names, mile markers, or way stations on the road to … wherever they might have been going?

One thing on which almost all commentators — midrashic, medieval, and modern — agree is that these place names are not actually the names of places! Although they all seem to describe Moabite topographic reality, none of them is specific, or related to any known site. Midbar (desert), Matanah (gift), Nachaliel (“arroyo of God” or strong wadi), Bamot (raised or high places), Pisgah (peak), Yeshimon (wasteland or desert escarpment). They seem, in the aggregate, to present a sort of map of life’s vicissitudes, from the flat desert to the peak of strength and visibility, falling back to a vast empty wasteland. Indeed, the talmudic sage Rava was pressured to explain these verses just before Yom Kippur in tractate Nedarim (vows, ironically, just before what came later to be the disavowal of vows known as kol nidrei). He explains that “when one becomes as selfless as the desert (midbar), he can be given the gift (matanah) of Torah, and inherit God’s companionship (nachali-el = ‘inheritance’ of God), but if he raises himself up high (bamot), he will find that he will be knocked down to the level of the flat plain (s’deh Moab), or even the empty wasteland (yeshimon).” Such an explanation is certainly a proper preparation for Yom Kippur, when we naturally think of choices we make that shape the broad vistas of our life, but does it give us any insight into the question of the poetic nature of these verses?

Looking, however, at the context of the parasha, with the deaths of Moses’ siblings, his troubles with the rock and water, the foreshadowing of his ultimate fate (not entering the land he’s been heading towards these past forty years), how can we help but see in these verses the heartbreakingly tragic scope of his life? For even Moses, the greatest of the Israelites, started out with nothing. He received his life as a gift, clutched from certain death in a basket floating on the Nile. He became God’s best friend and brought Torah to the world; yet he, too, was destined to face the vast wasteland, empty and depressed, the lowest point on the surface of the earth. The pathos, says Nietszche in his “Birth of Tragedy” — the book that describes his philosophy of art — is not when a baby dies or when a terrorist murders people for no reason. Tragedy, the ultimate art in life, is the ache we feel when we realize that even the greatest heroes, the pinnacles of human achievement, are subject to a senseless destiny, the end of their existence. As much as we try to structure what we do to keep the howling wilderness at bay, we cannot completely shut out the fearful chaos that crouches, drooling in anticipation for us all.

In this sense, these verses about traveling — the start from nothing, the undeserved gift that is life, the opportunity to connect as well as achieve, along with the inevitable drop to face the wasteland of oblivion — are one of the highest forms of art, appropriate for the waning moments of Shabbat or Yom Kippur. As the last rays of a darkening sun angle into the growing gloom, we find ourselves alongside Moses, hoping against hope to hold fast to all that we have cherished — our family, our career, our ultimate goal — as they slip through our weakening grasp. Now (too late?), we see how all that we had came out of a desert, presented to us as a gift. Even physics wonders at the existence of anything, an aberration arising from the quantum foam, a bubble as improbable as the inflated housing prices, that were gone in an instant. Can anything survive the relentless arrow of time?

One final commentary asserted that the huge emptiness into which a stunned Moses must have stared was large enough to contain a well or cistern. At the end of his journey, the boy who floated on water, who led his people through walls in a sea of water, who took his staff and hit a flinty rock bringing forth gushing water, he was presented with a vision of an emptiness that could cradle a well overflowing with water, enough to sustain future generations. Even as his star fades, the work of art that was Moses’ life, the Torah he brought down to confound all probability, will live on beyond his limitedness. As can we all, if we but use the improbable present we’ve been given to full effect. The end of the journey is determined, but what we do along the way is wide open, waiting for nobody but us!

Setting the Tone

David Bockman: Facilitating harmony

Lois Goldrich – Cover Story

Jewish Standard

of Passaic/Bergen County, NJ

Published: August 19, 2011

“I’ve always done a lot of musical things in whatever synagogue I work for,” said David Bockman, rabbi of Congregation Beth Shalom in Pompton Lakes. “It’s a part of how I am as a rabbi. Every rabbi is different in his job,” he added. Bockman, who has played trumpet since fourth grade, said he played in a number of bands at school — from marching bands to jazz ensembles to orchestras at school musicals.

“The high school had an orchestra,” he said. “A couple of us were music geeks. We didn’t sign up for the class, but we came in for the last rehearsal of the concert and they assumed we were good enough.”

To round out his musical endeavors, he also joined a medieval brass ensemble and a klezmer group. As an adult, his musical interest has become more focused. Today, he mainly plays jazz, klezmer, and rhythm and blues. “I don’t make a living as part of a band,” joked the rabbi. “I have this other job.”

Still, the two parts of his life often intersect.

“Some people view [the rabbi] as the CEO of a synagogue, but every rabbinate is different, depending on the rabbi’s skills and strengths. Part of my rabbinate is music,” he said.

Bockman incorporates music into religious services, puts on performances in and out of synagogue, and has brought musicians into the congregation. He also participates frequently in jam sessions, “hosted by different people, different nights, in different places.”

Being a rabbi, however, is never far from his mind, even when he’s jamming.

On Wednesday nights, he teaches Israeli folk dancing, “then I go out and hit a jam session. There’s jazz in Butler, rock in Oakland, and R&B in Linden.”

“It feeds back into my rabbinate — it would have to,” he said. “I get sermon ideas from playing. Most years on the High Holidays I devote one of my sermons to something I got out of music or trumpet playing. It’s an easy connection with the shofar.”

To Bockman, however, making music is not just a personal experience. Rather, “Music has always been part of the Jewish experience,” he said, although he is quick to add that “we don’t know what it sounded like in the Temple. We don’t know what the experience was like.”

While working in New Orleans, Bockman said, he was part of the local music community, inviting area musicians to his synagogue for jam sessions on such occasions as Purim. “It meant something to the musicians,” he said. “They asked about it every year” in anticipation of the event.

After his mother died, he invited fellow musicians to join him in a “jazz sh’loshim” program to honor her memory. Sh’loshim is Hebrew for 30 and is the name given to the month following a person’s death. Memorial services held at the end of that time are also called sh’loshim. It was “a beautiful musical experience in her memory,” he said. “It was unique, but it also felt like it grew organically from the Jewish tradition.”

After Hurricane Katrina, Bockman led a “New Orleans style” jazz funeral at Cooper’s Pond in Bergenfield before Selichot.

“It paved the way for the determination to change and better ourselves and the world, which are the core themes of Selichot,” he said.

“Music is an important part of my life,” noted Bockman. “It’s a way I can contribute to the Jewish community and the world. Sometimes we get too staid and insular and don’t reach out. My way is to be traditionally Jewish, but to bring this aspect into it.”

Bockman said that playing the trumpet, specifically, has affected his davening.

“Some of my congregants have commented to me that they’ve never seen someone as happy when they’re davening as I am, that I really ‘get into the experience.’”

In addition, Bockman said, “I can help knit together a group of people harmonically when everyone is playing or singing together.

“My contribution never works as well with me as the only or featured soloist, but rather as a facilitator of harmony, of enhancing a shared musical experience.

“I excel at playing with other musicians and helping them find music within them that they didn’t know they had. I feel I function in much the same way in prayer. That’s why the traditional prayer structure is preferable for me. As a skeletal structure, it can facilitate the flow of rich music that I can help the participants to weave as an ensemble. That’s how I approach Kabbalat Shabbat. “I don’t perform it so much as facilitate the weaving together of a community that invites and embraces Shabbat together.”